Did Kunta Kinte See His Parents Again

| Kunta Kinte | |

|---|---|

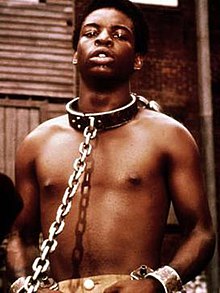

LeVar Burton as Kunta Kinte in the Television receiver miniseries Roots | |

| In-universe information | |

| Family | Omoro (father) Binta (female parent) Belle (wife) Kizzy (daughter) George (grandson) Tom (great-grandson) |

Kunta Kinte (c. 1750 – c. 1822; KOON-tah KIN-tay) is a character in the 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family past American writer Alex Haley. Kunta Kinte was based on one of Haley's ancestors, a Gambian human being who was built-in in 1750, enslaved, and taken to America where he died in 1822. Haley said that his account of Kunta'south life in Roots is a mixture of fact and fiction.[ane]

Kunta Kinte's life story figured in 2 U.Southward.-made tv set series based on the book: the original 1977 Tv miniseries Roots,[two] and a 2016 remake of the same proper name. In the original miniseries, the graphic symbol was portrayed as a teenager by LeVar Burton and equally an adult by John Amos. In the 2016 miniseries, he is portrayed by Malachi Kirby.[iii] Burton reprised his function in the 1988 TV movie Roots: The Gift.

Biography in Roots novel [edit]

Co-ordinate to the volume Roots, Kunta Kinte was born circa 1750 in the Mandinka village of Jufureh, in the The gambia. He was raised in a Muslim family unit.[4] [5] In 1767, while Kunta was searching for forest to make a drum for his younger brother, four men chased him, surrounded him, and took him captive. Kunta awoke to find himself blindfolded, gagged, spring, and a prisoner. He and others were put on the slave send the Lord Ligonier for a 4-month Middle Passage voyage to North America.

Kunta survived the trip to Maryland and was sold to John Waller (Reynolds in the 1977 miniseries), a Virginia plantation owner in Spotsylvania County, who renamed him Toby (named by John's wife Elizabeth in the 2016 remake). He rejected the name imposed upon him by his owners and refused to speak to others. Later being recaptured during the final of his four escape attempts, the slave catchers gave him a pick: he would exist castrated or have his right human foot cut off. He chose to have his foot cutting off, and the men cut off the front end one-half of his right foot. As the years passed, Kunta, now endemic by John's brother Dr. William Waller, resigned himself to his fate and became more open and sociable with his beau slaves, while never forgetting his identity and origin.

Kunta married an enslaved woman named Belle Waller and they had a daughter named Kizzy (Keisa, in Mandinka), which in Kunta'southward native language means "to stay put", to protect her from being sold away. When Kizzy was in her belatedly teens, she was sold abroad to Due north Carolina when William Waller discovered that she had written a fake traveling pass for an enslaved beau, Noah, with whom she was in love. She had been taught to read and write secretly by Missy Anne, the niece of the plantation owner. Her new owner, Thomas Lea (Moore in the 1977 miniseries), immediately raped her. He fathered her but child, whom he named George after his first slave (or afterward his own male parent, according to the 2016 miniseries). George spent his life with the tag "Chicken George", because of his assigned duties of disposed to his master's cockfighting birds.

In the novel, Kizzy never learns her parents' fate. She spends the remainder of her life every bit a field hand on the Lea plantation in North Carolina. According to the 1977 miniseries, Kizzy is taken back to visit the Reynolds plantation later in life. She discovers that her female parent was sold off to some other plantation and that her father died of a broken eye ii years after, in 1822. She finds his grave, on which she crosses out his slave name Toby and writes his existent proper name Kunta Kinte instead. Kizzy is Haley'southward only ancestor in the genealogy link to Kunta Kinte, who spent the bulk of his life in slavery.

The latter part of the book tells of the generations between Kizzy and Alex Haley, describing their suffering, losses, and eventual triumphs in America. Alex Haley claimed to be a seventh-generation descendant of Kunta Kinte.[half dozen]

Historical accuracy [edit]

Haley claimed that his sources for the origins of Kinte were oral family unit tradition and a man he plant in the Republic of the gambia named Kebba Kanga Fofana, who claimed to be a griot with knowledge virtually the Kinte clan. He described them every bit a family in which the men were blacksmiths, descended from a marabout named Kairaba Kunta Kinte, originally from Mauritania. Haley quoted Fofana as telling him: "Near the time the king'due south soldiers came, the eldest of these 4 sons, Kunta, went away from this village to chop wood and was never seen again."[vii]

However, journalists and historians later discovered that Fofana was not a griot. In retelling the Kinte story, Fofana changed crucial details, including his father's name, his brothers' names, his age, and fifty-fifty omitted the year when he went missing. At one point, he fifty-fifty placed Kunta Kinte in a generation that was alive in the twentieth century. It was also discovered that elders and griots could not requite reliable genealogical lineages earlier the mid-19th century, with the single credible exception of Kunta Kinte. It appears that Haley had told and then many people virtually Kunta Kinte that he had created a case of round reporting. Instead of independent confirmation of the Kunta Kinte story, he was actually hearing his ain words repeated back to him.[8] [9]

After Haley's book became nationally famous, American author Harold Courlander noted that the section describing Kinte's life was apparently taken from Courlander's own 1967 novel The African. Haley at offset dismissed the charge, but after issued a public statement affirming that Courlander'due south volume had been the source, and Haley attributed the error to a mistake of one of his banana researchers. Courlander sued Haley for copyright infringement, which Haley settled out of courtroom.

Nonetheless, despite the inconsistencies with Haley's chronology, Kunta Kinte was probably a existent person. According to historian John Thornton, director of the African American Studies plan at Boston University (who served as a historical advisor to the 2016 remake of Roots), the historical Kunta Kinte was indeed from the town of Jufureh, which was then part of the Kingdom of Niumi, and was from a Muslim Jula family which had moved there a generation earlier his birth. He came from a family of merchants who were involved in all matters of commerce, including the slave trade. He was sold into slavery effectually 1767. Information technology is remarkable that he was sold into slavery given his family's social status as heart class merchants, as well equally the ongoing debate at the time regarding whether it was permissible to sell Muslims every bit slaves to Christians, and his beingness sold into slavery peradventure had something to practice with inter-factional disputes amidst the Jula or traders, too as the dispute Kingdom of Niumi had with a Majestic African Company trading mail at the time, during which the two sides seized hostages.[10]

In pop civilisation [edit]

Kunta Kinte has inspired a reggae riddim of the same name. This started off life as a track called Beware Of Your Enemies released from Jamaica's Channel One. A dub version, put out in 1976 by Channel One house ring The Revolutionaries became a audio system anthem for many years on dubplate, and inspired a UK version produced by Mad Professor in 1981. It has as well inspired jungle covers.[xi]

There is an annual Kunta Kinte Heritage Festival held in Maryland.[12]

The 1988 comedy movie Coming to America jokingly references Kunta Kinte, in an homage to Roots (John Amos, who played a supporting role in Coming to America equally the father of the protagonist'due south love involvement, played the developed version of Kunta Kinte in the 1977 miniseries).[xiii]

Kendrick Lamar's 2015 song "King Kunta" was inspired by the graphic symbol. Afrikan Boy released a song called Mr. Kunta Kinte in 2016 [xiv]

Athlete Colin Kaepernick wore a T-shirt with "Kunta Kinte" emblazoned on it to his controversial NFL tryout. In CNN'due south interpretation, "Kaepernick appeared to apply the reference to brand a statement: He will not change who he is to appease the powers that be."[15]

See besides [edit]

- Kunta Kinteh Island in the The gambia

- List of slaves

References [edit]

- ^ The Roots of Alex Haley". BBC Television Documentary. 1997.

- ^ Bird, J.B. "ROOTS". Museum.tv . Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ Campbell, Sabrina (May xxx, 2016). "Malachi Kirby is Kunta Kinte in 'Roots' Remake". NBC News. Retrieved Jan iii, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Griselda (2014). "The Influence of Malcolm X and Islam on Black Identity". Muslims and American Popular Civilisation. ABC-CLIO. pp. 48–49. ISBN9780313379635.

- ^ Hasan, Asma Dupe (2002). "Islam and Slavery in Early American History: The Roots Story". American Muslims: The New Generation Second Edition. A&C Blackness. p. xiv. ISBN9780826414168.

- ^ "The Kunta Kinte – Alex Haley Foundation". Kintehaley.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ^ Alex Haley, "Blackness history, oral history, and genealogy", pp. 9–nineteen, at p. 18.

- ^ Ottaway, Mark (April 10, 1977). "Tangled Roots". The Sunday Times. pp. 17, 21.

- ^ Wright, Donald R. (1981). "Uprooting Kunta Kinte: On the Perils of Relying on Encyclopedic Informants". History in Africa. 8: 205–217. doi:x.2307/3171516. JSTOR 3171516.

- ^ Kunta Kinte's World

- ^ "Riddimology 001: "Kunta Kinte"". Dub-stuy.com. Baronial 5, 2018.

- ^ "Kunta Kinte Heritage Festival". Kuntakinte.org. Kunta Kinte Celebrations, Inc. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Aquino, Tara (June 29, 2018). "ten Fun Facts About Coming to America". Mental Floss. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Afrikan Boy - Mr. Kunta Kinte - YouTube". YouTube.

- ^ Levenson, Eric (November 17, 2019). "Why Colin Kaepernick wore a 'Kunta Kinte' shirt to his NFL workout". CNN . Retrieved Feb 14, 2020.

External links [edit]

- The Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley Foundation

pruittpontliatich.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunta_Kinte

0 Response to "Did Kunta Kinte See His Parents Again"

Post a Comment